I learned a thing or two about the way Public Relations works hand in hand with websites, magazines, etc. When talking with a PR agent this past year I realized that it’s their job essentially to create a narrative about the artist that existed outside of the actual work being promoted. In other words, I needed some kind of lurid, profligate, or peculiar angle to sell the idea of my band to a hip site. Did I cut my head open while playing? Was my mother famous or she die in some horrific fashion? Did we ever get arrested for something funny that would make a great story? This is the way media seems to work; it looks for a tabloid report to tack onto the release of an artist’s work. Then as I would read these cover stories from Rolling Stone or Pitchfork I could immediately see it, some story or allegation to rest the entire piece on rather than an invested interest in the work at hand. It is how many syndicates employ their staff and how they create a larger narrative for the artists they promote. It’s a “you scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours” system and Lars Von Trier is one of the best at playing along.

He knows damn well that by becoming a household scoundrel he is also giving his films that extra boost to reach a wider audience without necessarily having to compromise his visions (though I’m sure many would argue this point). He, like Tarantino, knows how to sensationalize legitimate artistic endeavors in our modern film culture risking their names in the process. Think about his last three projects on paper, as proposed to those of us who read Indiewire, Slant, etc. His first was a horror film that outdid the modern splatter scene at their own game when the violence actually kicked in which outside of the opening sequence was pretty much only the final 20 minutes, adding real sex and genital mutilation to further complicate the madness. People fainted in the aisles and the director howled from the rooftops that he was greatest living director in the world, eliciting an all too easy response which led to more media coverage than even Tarantino’s Nazi scalper epic could conjure. It also elicited a very mixed critical reaction, one that found very little middle ground in its initial run (of course the aftermath of such a film finds more sober reactions surfacing once the hysterics die down). Either critic’s loved it or hated it, a line seemed drawn in the sand. That the film has been getting more and more reverence as time distances us from the preconceived PR campaign may be a testament to the fact that his devious plan may have worked. The second was about the end of the world, and while the content was admittedly hushed compared to his previous effort, he made up for this by getting himself banned from France at the Cannes press conference by saying some incredibly stupid shit to piss off the easily rattled targets.

My point in all of this would be to point out that the man will do any brazen exploit to ensure his work is seen and reckoned with. He isn’t interested in making something slight anymore, he doesn’t want his work to slip between the cracks. He’s also addicted to the limelight and willing to stage the most petty and immature stunts imaginable to ensure that other films simply get buried beneath his ego. At the same time we have to look at the success of these stunts. In this way Von Trier seems a step ahead og the game, a true entrepreneur, realizing that alienating certain reactionary sects might allow his work to be examined in the history books without the viral frenzy to cloud the rest of our judgment. He knows that time heals all wounds, that all art will eventually speak for itself. In the case of both of these films, each a brutal and uncompromising vision with all of the paltry baggage sprinkled in and saved for some by reflective/brooding flourishes, he got the debate raging.

These two films were battles waged within, an introspective approach that felt refreshing after his finger pointing society-is-fucked morality tales. For once Von Trier appeared truly concerned with his own trajectory and inner turmoil in relation to his past and present predicaments, and both served as an outlet to exorcise his spiritual/mystical/moral angst. Now I’m wasting your time by explaining the artistic process, but I assure you it’s all for the purpose of pointing out that while I have found all of his work extremely problematic, I’d take a sloppy, honest, and personal vision over just about any other kind any day of the week. For all of his cheap tricks he lays himself disconcertingly bare.

His latest is a PR dream come true is NYMPHOMANIAC. The title alone ensured it’s press, a supposed 4 hour art porno. Jesse and I gave a try. If you lump this film along with the other two aforementioned projects you could call it the “learning to accept myself and all of my flaws” trilogy. It opens with the sound of rain dripping off of gutters and down brick walls, immediately calling to mind the factories of STALKER until Rammstein abruptly overpowers the sounds of chilly dampness. Von Trier patiently scans the area, building tension with the sound of cold condensation until finally revealing a trodden lifeless body amongst the puddles. She is discovered by a man and taken to his apartment to recover where she recollects her story in flashback, slowly learning how she got where she is.

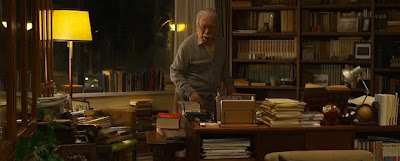

You could probably gather from the title of the film that her story fixates on her various sexual experiences, but it’s more interested in reading memories and making psychosomatic sense of their impact on who this woman is. It’s also about unapologetically confessing one’s misdeeds while correspondingly begging someone to challenge and correct your path. It’s a film at war with itself, a movie about battling whims and deep psychological wounds. The woman (Charlotte Gainsbourg) is the director’s proxy and the man (Stellan Skarsgard) is his mentor. Von Trier is having a little chess game with himself, disputing his impulses (the side that clips the nails on the left hand first and the side that likes to fly fish) and letting us watch. It’s hard to know what narrative embellishments come from the director’s past but it all feels autobiographical with many of the actions changed to fit the film. Jesse pointed out that by using the flashback apparatus he was probably forced to enliven things visually in ways he hasn’t before, and this probably elevated everything beyond what we thought it capable of. NYMPHOMANIAC features plenty of new tricks, most of which helped along by the Fibonacci Sequence’s contrived inclusion to the storyline (Jesse knew it Fibonacci was on the horizon when he heard 3 and 5, I felt very stupid watching this film with him).

It’s a neat trick, one that allows breaks in continuity and visual scheme. The events are built upon algorithms involving ash trees, Bach, fly fishing, and loin thrusts. In all of this there exists connections and excuses for more Tarkovskian underwater flora, a dick montage, and some nifty jaguar/antelope footage to zest up the proceedings. This is one of his many ways of ensuring that his career won’t be boxed in by the festival circuit’s expectations. This impish quality can be grating at times, none more so than the Uma Thurman scene where she acts like Piper Laurie out of CARRIE. In that chapter we are supposed to finally question the woman’s careless game because one of her lover’s is a married man with two children. The wife brings the kids to her apartment and calls out her husband and makes the children watch, it’s supposed to shock us but the scene is so daffy and out of step with the rest of the film that the mentor’s unwarranted shock feels like a fraud. We can see why the husband has left her right from the moment she first speaks and whatever sympathy we could have had for the resentful wife drifts away. It would have worked better and have developed a more transparent dilemma for the audience.

I had plenty of little problems with the film, as I do with most of his work (it seems borderline cruel to ask Shia Lebouf to do an English accent) but as I said before, he has a fascinating messiness to him. It’s that same quality that preserves his vitality as an artist. It keeps his films alive. He’s constantly challenging and destroying things that he builds up. He is a heretic unto himself. Nothing seems to irritate him more than the algorithms that “self-deluding liberal humanists” or “hypocritical petty commoners” seem to expect from him film to film. He seeks to shatter all dogma’s and reaffirmations that were once expected of him. Here it’s as if he’s saying “all is love” and “all is grace” while whispering in our ear “forget about love” and “grace is for hippies.”